This article is part of a five-part series on prison labor.

When Congress passed the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865, they included a crucial exception clause that allows for slavery and involuntary servitude as punishment for crime. This clause has resulted in the forced labor of millions of people in our prisons and jails since, and the first beneficiaries of this labor were private corporations.

The exception clause allowed states, often in the South, to pass Black Codes, laws that specifically criminalized Black life and filled jails with Black people. States then used “convict leasing” to rent incarcerated people to private individuals and corporations looking for cheap labor, often plantations. By the late 1800s, states like Alabama were deriving more than half of their revenue from “convict leasing.”

The practice would soon fall out of favor with the public, but the depression era of the 1920s created a new demand for prison labor. With businesses struggling, few jobs available, and manufacturing lagging, governments began using prison labor for everything from infrastructure construction to consumer goods production to agricultural farming. But the private sector quickly complained that prison labor gave governments an unfair advantage, and by the mid 1930s, Congress passed legislation that regulated prison-made products and prohibited their sale into interstate commerce – with a key exclusion for agriculture.

That is until 1979, when Congress introduced the Prison Industry Enhancement Certification Program (PIECP) to allow corporations to once again use prison labor and the practice resurfaced broadly. Today, prison slavery produces billions of dollars for the economy with many corporations taking advantage directly or participating in the supply chain of products manufactured in prisons. And though it is the smallest group in the prison labor empire, there are still thousands of incarcerated people working for the benefit of private corporations.

PIECP and Its Corporate Partners

While PIECP is a federal program, it is overseen by the National Correctional Industries Association (NCIA), a member-based private association of prison administrators and corporations. In other words, those benefiting from PIECP worksites are also responsible for monitoring their own compliance with the program’s legal guidelines.

NCIA lists 74 corporate members, starting with mega-conglomerate 3M (NYSE: MMM), which is a corporate plus member, the highest level membership available at the association. Other recognizable brands include packaging and adhesives manufacturer Avery Dennison (NYSE: AVY), office furniture manufacturer Dauphin, and Burlington Industries, owner of the iconic Burlington Coat Factory.

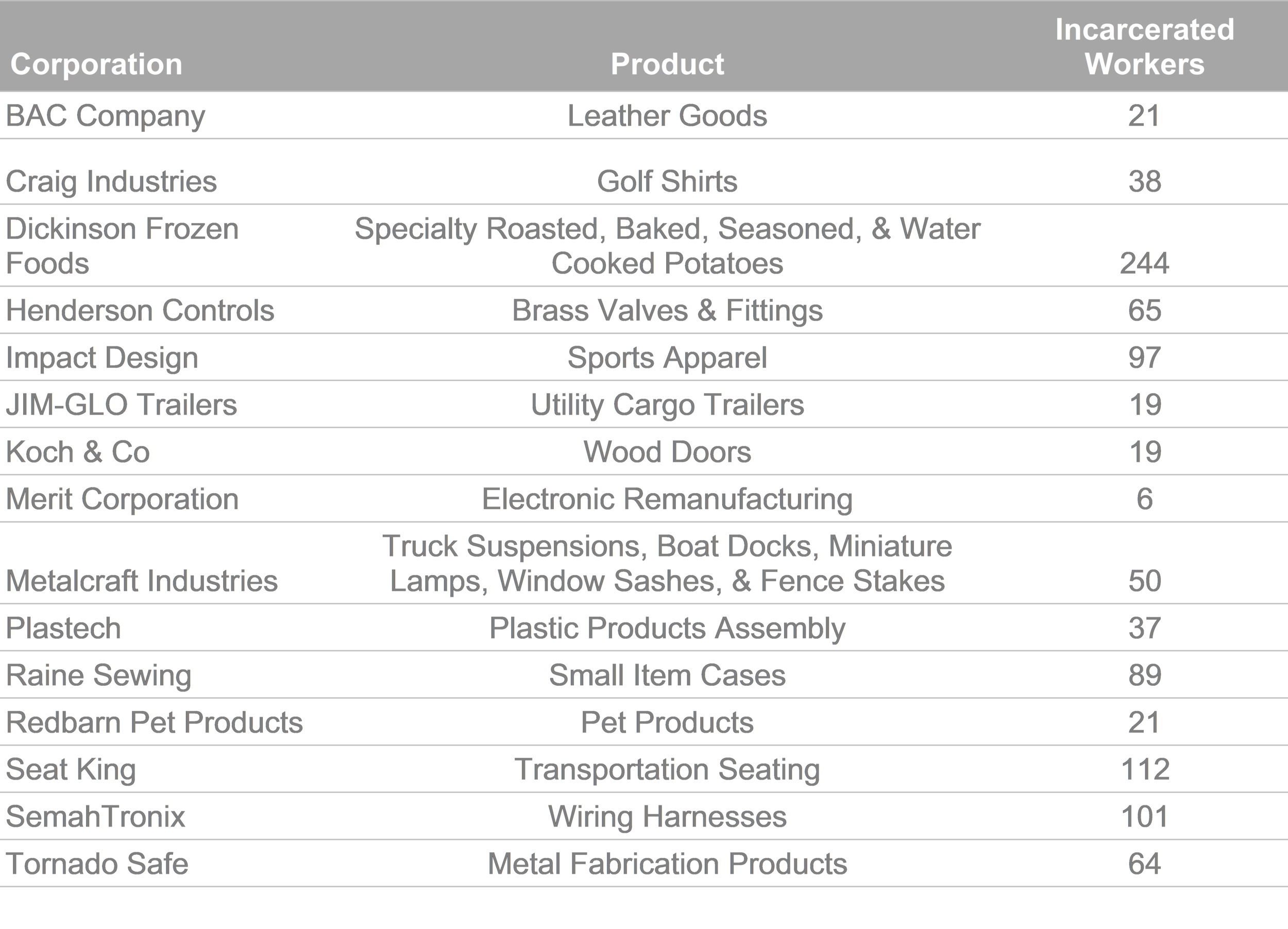

NCIA provides a quarterly list of the corporations running certified PIECP worksites and the products each manufactures using prison labor. Some corporations active in the first quarter 2021 include:

While we might only recognize a few of these corporations, many are unknown suppliers to top-tier brands that are not named PIECP participants. Dickinson Frozen Foods, for example, uses prison labor to package potatoes that are later distributed to household food brands like Pillsbury and Campbell Soup. Seat King is a supplier to industrial lawn mower manufacturer Husqvarna. SemahTronix sells its wire harnesses to GE and Philips.

Still, many corporations manage to keep their names out of these quarterly reports entirely by operating in states where correctional administrators will not reveal their corporate partners when reporting PIECP data to the NCIA. That’s how prison labor champion 3M has evaded scrutiny for years in Minnesota, which in most cases only lists the name of the facility and a general product description in its reports.

Wages Are Only Part of the Story

Corporations that use prison labor through PIECP are required to pay prevailing wages, which cannot be lower than minimum wage, but also are rarely higher. And yet, low wages are just part of the equation, participating corporations do not have to pay for benefits or workers compensation, concern themselves with employee absences, or worry about employee grievances as they would in broader society.

When describing the benefits of prison labor, the owner of Lockhart Technologies, a corporation that partnered with private prison operator GEO Group in the mid-90s to use prison labor to manufacture electronic and computer parts, put it bluntly: “Normally when you work in the free world, you have people call in sick, they have car problems, they have family problems. We don’t have that [in prison.]” Indeed, Lockhart saw such immense savings in personnel costs with prison labor that it shut down an outside plant.

And it’s not just participating corporations that cash out. PIECP wages can be garnished by the government for a variety of purposes. According to NCIA’s data, since the program’s inception, incarcerated workers in PIECP jobs have earned $990 million in gross wages and had $582 million, or 59%, garnished. The largest garnishments by far – $315 million, or 54% of all garnishments – are for “room and board.” These are funds retained by participating correctional agencies, which drives their interest in the program.

While corporations and correctional administrators rake in millions through PIECP, incarcerated workers are left with less than half of their earned income, their basic needs in prison unmet, and their families struggling to support them and themselves. So, while PIECP jobs are still generally considered to be among the highest paying for incarcerated workers – and thus highly sought after by incarcerated people forced to work with limited choices – as the Bureau of Justice Assistance itself admits, all the “parties other than the inmates themselves are the first beneficiaries of PIECP inmate income.”

Unregulated Corporate Gain

The failures of PIECP extend not just to the corporations directly using prison labor and those that benefit down the supply chain but also to the corporations that are upstream suppliers. These benefactors of prison labor supply equipment and raw materials to government-run prison businesses that produce everything from license plates to university furniture. For instance, since 2018, 3M has sold $3.3 million in “materials used in the production of goods for sale or use by the State” to just CorCraft, New York’s correctional business. With PIECP exclusively regulating the private sector’s direct use of prison labor, this type of profit falls off the radar.

Finally, there are those corporations outside PIECP’s scope entirely. PIECP regulations do not apply to service or agriculture jobs. In 2020, then-presidential candidate Mike Bloomberg was exposed for using prison labor to make campaign calls. His campaign had contracted ProCom to provide call center services. The corporation used incarcerated women in Oklahoma to make the calls. ProCom’s use of prison labor is not covered in NCIA reports or regulated by any federal or state law. As such, there is no data about the number of corporate service and agriculture jobs in prisons and jails across the country.

***

The bottom line is that it is impossible to have a firm grasp on every corporation that exploits and benefits from prison labor. For every one that is exposed, it’s likely that hundreds or even thousands remain unknown. That’s why we must call for an end to the corporate abuse of forced prison labor and end the exception in the Thirteenth Amendment that got us here.

The #EndTheException campaign is proud to offer wrapping paper that depicts the evolution of historical slavery and resistance. Purchase this wrapping paper and start an important conversation with your loved ones this holiday.